Mathematics in the Scientific Worldview

On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica And Related Systems

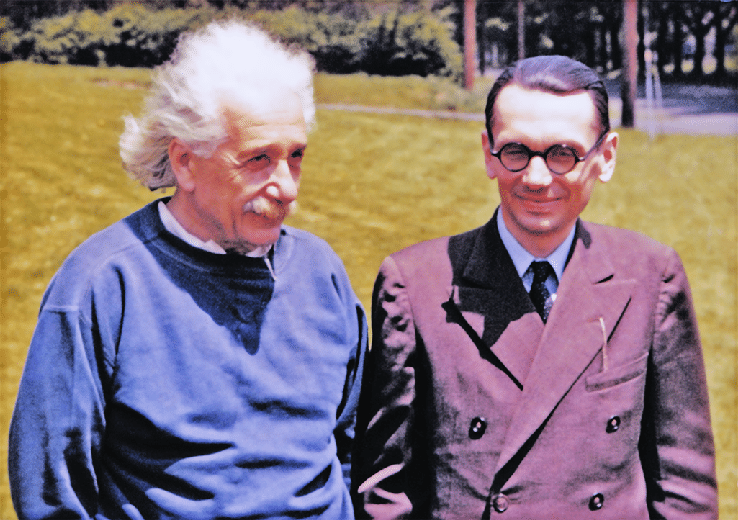

By: Kurt Gödel

A Summary by: Constantino Themelis

Kurt Gödel’s 1931 incompleteness proof is one of the greatest feats in the history of logic and mathematics. In short, he proved that in any formal logical system capable of expressing elementary arithmetic, there exist arithmetic propositions that are true yet cannot be proved or disproved in the system. For many that’s where their knowledge ends, but the true brilliance of Gödel’s work can be found in the nitty gritty details.

Let us begin by portraying the arms race occurring at the time in mathematics between the logicists, intuitionists, and formalists. The foundations of mathematics seemed to be at the tip of humanity’s fingers in 1930, with Hilbert’s formalist program (which sought to explain mathematics as a system of established rules for manipulating symbols) sure to come to their complete proof of the foundations of arithmetic anyday. Logicists like Hans Hahn and Bertrand Russell too believed that we could reduce mathematics to pure logic and continued to work on proving their ideas. To put it lightly, Gödel flipped the entire field of mathematics on its head. His findings overturned the prevailing belief that mathematics could be both complete (every true proposition is provable) and consistent (no contradictions) using the arithmetic of Principia Mathematica (Russell, Whitehead) extended with the Peano axioms (system P). His methods were later generalized by the likes of Carnap to any formal system meeting broad criteria.

Gödel constructs a formal system in the proof, let’s call it P. The structure includes basic signs, well-formed formulas built from the symbols using construction rules, axioms, and rules of inference. He uses axiom schemata to cover infinitely many axioms instances following the methodology of famous formalist John Von Neumann. Overall the details of P are not important, however we need to establish that P does represent ordinary number theory.

The brilliance of Gödel is what is commonly called ‘arithmetization. Each symbol was designated with a number, and he extended this numbering to both his formulas and proofs using prime factorization. Every syntactic object therefore had its own unique number, coined ‘Gödel number’ later on. On a metamathematical level, relations correspond to exact numerical relations between Gödel numbers. The arithmetization of the syntax of the proof meant that purely metamathematical statements could be expressed arithmetically within the system. In other words, the system could talk about its own proofs and formulas.

I’ll move on briefly to primitive recursive functions and relations, which Gödel works with in his proof. Recursion in Gödel’s context refers to the method of defining functions or relation on natural numbers in terms of simpler cases of themselves. This enables their stepwise computation and representation within a formal system. In his 5th proposition, he shows that every recursive relation is representable within P, which means there exists a formula corresponding whose provability mirrors the truth of the relation. The representability results of associated provable (or unprovable) formulas ensures that the syntactic machinery of P can capture the behavior of the recursive computations within the deductive framework of P itself.

To construct the famous undecidable sentence, Gödel does the following reasoning, which is extremely generalized for the sake of simplicity: If P is consistent then an axiomatized theory strong enough to represent arithmetic, then there is a sentence G in P which says “I am not provable in P”. If P proved G, it would prove something false about its own provability, contradicting consistency. If P proved notG, then it would prove that G has a proof, which contradicts consistency. Therefore, G is not provable or disprovable, making P incomplete.

The second incompleteness theorem builds on the first by formalizing the statement “P is consistent” inside P. Gödel shows that if P could prove “P is consistent” then P could proved the unprovable Gödel sentence thus contradicting consistency. Therefore if P is consistent then “P is consistent” is true but unprovable within P. This generalizable result then allows us to say that no system can from within itself, give a proof that is free from contradiction.

Gödel’s proofs are syntactic, but when P is interpreted as expressing arithmetic, the undecidable formula corresponds to a true arithmetical proposition, if we assume the axioms of Principia and Peano are true.

The result here is astonishing. Incompleteness would become a fundamental feature of arithmetic, and essentially ended the great quest for the foundations of math. Gödel also inadvertently helped to advance logic and computability theory. His diagonalization, use of recursive functions, and arithmetic designation system deeply influenced the likes of Alonzo Church and Alan Turing. Less well known was Gödel’s motives in doing this proof. He clearly had an idea of the result, and had to find a way to prove it, however Gödel was also a platonist. It’s likely that Gödel sought to prove Plato’s ideas of forms, and particularly place mathematics purely in the platonic worldview. Whether or not his results made him successful in doing so is up for debate, but regardless his intentions remain fascinating. Gödel’s proof is one of the greatest feats of humanity to this date, and his results had a profound impact on the logical empiricists and how they conceived of mathematics.

I must finish by stating that summarizing Gödel’s Incompleteness Proofs was no easy task. I was aided by Professor Nathaniel Mull, Professor Derek Anderson, and the Boston University Logic Reading Group. Our Spring 2024 Logic Circle went through a painstaking line by line analysis of the proof which aided my understanding in an immeasurable way.