The Leaders of the Logical Empiricism Movement

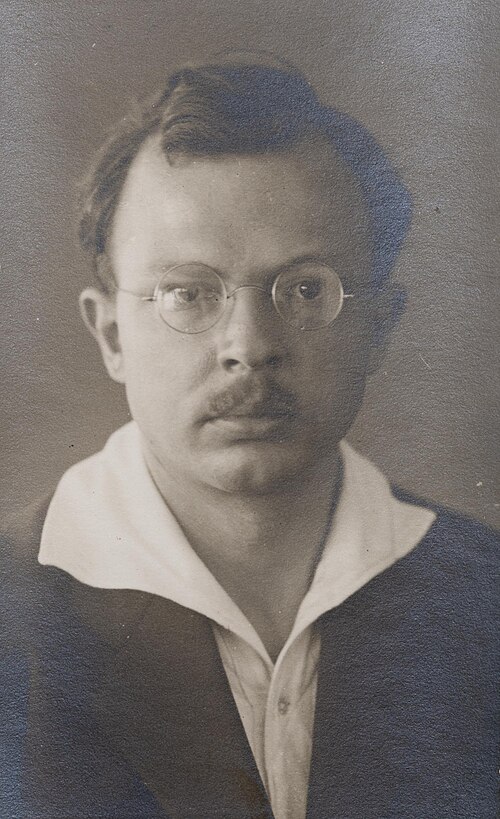

Moritz Schlick (1882-1936)

Moritz Schlick was a German philosopher and physicist, well known for his work on Special Relativity and philosophy of science. He Is given credit for founding and giving figure to the Vienna Circle, the group of philosophers who met in the 1920s and 1930s to discuss a new philosophical movement, logical empiricism. Schlick’s academic training was under the physicist Max Planck in Berlin, where he achieved his PhD in 1904. He later transitioned to philosophy, where he received his habilitation at the University of Rostock. Thereafter he wrote two of his most famous books, “Space and Time in Contemporary Physics”, about geometric conventionalism in the general theory of relativity, and “General Theory of Knowledge”, one of the earliest works of positivist epistemology. After General Theory of Knowledge, which emphasized clarity, logic, and the rejection of metaphysics, Schlick was appointed to be Chair of Philosophy of the Inductive Science at the University of Vienna. It was at this point in 1922 that he gathered a circle of thinkers with the help of Hans Hahn. By 1928 the group become a force in the intellectual community of Vienna, with other like Rudolf Carnap, Otto Neurath, and Kurt Gödel regularly attending meetings. Together they met to advance the “scientific worldview,”holding that all meaningful proposition must be grounded in empirical verification. Schlick was admired across the glove for his clarify of thought, as well as his ability to unite scientists and philosophers. His life tragically ended in 1936, when a former student assinatted him on the steps of the University of Vienna in 1936. Schlick could have departed what was becoming a racist Vienna far before this point, but his commitment to his community kept him teaching at the place he loved. Moritz Schlick was the anchor of the Vienna Circle, and remains one of the greatest positivist thinkers of the 21st century.

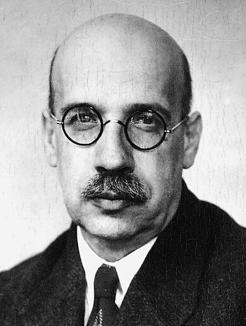

Rudolf Carnap (1891-1970)

Rudolf Carnap was born in Düsseldorf, in what was then the German Empire. His father was a poor ribbon-weaver, and his mother came from an academic family. In 1910 he enrolled at the University of Jena, studying physics, while also taking classes from Kantian Bruno Bauch and a little known logician Gottlob Frege. After serving in World War 1, he studied at the University of Berlin, where he became politically active in left-wing circles. He then returned to Jena where he wrote a thesis on axiomatic theory of space and time, but it was deemed too philosophical for the physics department to pass it off as legitimate physics. He decided to write another thesis with the help of Bauch on a Kantian theory of space and time. His time as a Kantian would end soon after, as Frege’s course on logic turned him toward logic in philosophy. After some influence by the work of Bertrand Russell, Carnap became convinced that philosophy should adopt the precision of the sciences. Carnap went on to write the Aufbau in 1928, which attempted to reconstruct all scientific concepts from elementary experiences using logical definitions. Carnap would then meet Han Reichenbach in 1923 at a conference, where he met Moritz Schlick who offered him a job at the University of Vienna. There he became a core member of the Vienna Circle and continued the mission of unity of science, helping to articulate its goals. Due to Nazi suppression, Carnap had to emigrate to the United States in the early 30s. There he helped logical empiricism spread like wildfire, holding positions at UChicago, Harvard, and UCLA. During his time in the States he wrote Logical Syntax of Language and Meaning and Necessity, which advanced the use of formal logic and explored concepts like semantics and modal logic. Carnap’s rigor and dedication to scientific philosophy made him arguably the most influential figure in 20th century analytic philosophy.

Hans Hahn (1879-1934)

Hans Hahn was born in Vienna as the son of a government official. He did his studies in mathematics, and got his PhD at the University of Vienna in 1902 under Gustav von Escherich. After getting his degree he taught in Innsbruck and Czernowitz, until he joined the Austrian army in 1915. During World War One he was badly injured, and returned to teaching in Bonn. Finally he returned to Vienna in 1921 as a Professor, where he remained until his unexpected death from surgery in 1934. Hahn’s major contributions to academics come in mathematics, include a plethora of important theorems including the Hahn-Banach theorem and the uniform boundedness principle. Beyond his vast success in mathematics, he took a keen interest in philosophy, namely Mach’s positivism. With Otto Neurath he helped bring Schlick to Vienna and facilitated the creation of the first “Schlick Circle” which would become the famous Vienna Circle in 1924. As an advisor his most famous student was Kurt Gödel, who frequented Vienna Circle meetings. Hahn was deeply engaged with the philosophy of science, seeking like others in Vienna at the time, to unite philosophy with the methods of logic and science. Hahn himself was a logicist of the Russellian strand. In his personal life he was an avid socialist, and sought to research extrasensory experience (must to the chagrin of his colleagues). His contributions in mathematics and philosophy, and his presence in Viennese academic life make him a significant figure in the history of logical empiricism.

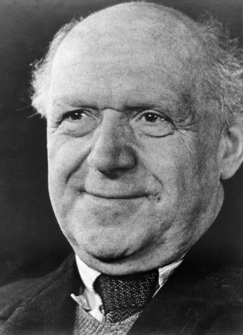

Otto Neurath (1882-1945)

Otto Karl Wilhelm Neurath was born in Vienna, in the heart of what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was the son of a well known political economist, and would follow in his footsteps becoming a political economist himself, as well as a philosopher of science and sociologist. Neurath studied at the University of Vienna in mathematics and physics, and in 1906 he gained his PhD from the University of Berlin in political science and Statistics. The New Vienna Commercial Academy was where he began teaching, but after doing his habilitation thesis at Heidelberg he decided to shift to museum curation in Leipzig. He would continue to work in museums the rest of his life. Neurath was very politically active throughout the early 20th century, joining the German Social Democratic Party and running for office as a central economic planner. This brought him to Munich where he was part of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, and during t’s collapse he was imprisoned and returned to Austria. This didn’t deter Neurath from his activism, as he became the secretary for small gardens in Red Vienna and curated exhibits for the government. Neurath’s main goal was to make the museum accessible to everyone in the diverse Austro-Hugarian Empire, no matter what language they spoke. The solution was his “ISOTYPE” language, International System of Typographic Picture Education. He essentially created the concept of infographics, using icons to represent quantitative data, which he incorporated into his widely popular museum exhibits. In the 1920s he became a logical empiricist and the secretary of the Vienna Circle. His famous contribution was in the form of protocol sentences, which were motivated by his believe that experience should have a third person and public character rather than being completely subjective. Being a radical physicalist and believer in the unification of the sciences, he believed in the construction of a universal system which could encompass all knowledge with the help of the sciences. but rejected any isomorphic interpretation of the relationship between language and reality. This put him at odds with the likes of Wittgenstein, but influenced W.V.O Quine profoundly. Reality to Neurath was all the previously verified propositions, and if a proposition conferred with the already verified sentences, then it could be considered true. Coherentism was therefore pioneered by Neurath and developed by Quine decades later. There are not enough words to describe how eclectic, unique, and incredible Otto Neurath was. His influence ranges from philosophy all the way to economics, and he is certainly under appreciated in the canon of logical empiricism.

Philipp Frank (1884-1966)

Phillipp Frank was born in Vienna in 1884. He studied physics all the way through his time as a student, graduating with a PhD in theoretical physics in 1907. His advisor was Ludwig Boltzmann, another late 19th century physicist revered by the logical empiricists. It was likely this influence that led Frank to positivist views as well as his studies of the work of Ernst Mach. It was alongside Mach that Frank was critiqued by Vladimir Lenin in his work, Materialism and Empirio-criticism, which accused Frank and Mach of being solipsists. Of course Frank denied this characterization of his view, although as a socialist he held a great respect for Lenin and Marxist philosophy. In 1912 he left Vienna to succeed Albert Einstein at his recommendation for a Professor position at the German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague. In 1938 Harvard University invited Frank to lecture on quantum theory and modern physics, and he would never return to Prague. Days after he left, the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia occurred, and as a Jew, he was unable to return. At Harvard Frank would be a Professor until he retired in 1954. Going to the states didn’t hamper Frank’s belief in the logical empiricist program. In 1947 he founded the Institute for the Unity of Science within the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The institute held events across the West, and served as the stage where the members of the Vienna Circle would meet post World War Two.